Home | Front Page | Index | Blog | New | Contact | Site Map

USA 2003

Virginia 2003 |

Photos |

Map

Richmond

Lee's Retreat

Appomattox Ct

Lynchburg

Red Hill

We went to Richmond for the same reason that other people climb mountains: because it was there. Or more precisely, on our route from New York, New Jersey, and Washington, DC to the south: the Carolinas and Florida. As we suppose of the chicken who crossed the road, we are glad that we did because Richmond has a rich history, always a plus for us, and we were glad to take a few days to increase our understanding of it.

Richmond, State Capital

Virginia State Capitol Building |

Twice Richmond has been selected as a capital and twice it was because of location. The first time was as Virginia's capital in 1780 because it was on the farthest point inland on the biggest navigable river in Virginia, the James.

The photos here are of the Capitol building, designed by Thomas Jefferson, completed in 1788 and extended in 1906, and of statues that adorn the gardens that surround the Capitol.

Major statue on grounds of Virginia Capitol |

Detail of statue on grounds of Viriginia Capitol |

Richmond, Capital of the Confederacy - Jefferson Davis Home

Jefferson Davis House |

Richmond's second time as capital was as the capital of the Confederate States of America (often shortened to "the Confederacy" and known familiarly as "Old Dixie"). Richmond was chosen because unlike its predecessor, Jacksonville Alabama, it was close to that other capital, the one on the Potomac. Its position as capital of Virginia has endured of course while that as capital of the Confederacy collapsed with the defeat of the breakaway slave s$tates.

The photos here are of the house in Richmond where Jefferson Davis, the President of the CSA, lived with his family.

Jefferson Davis House |

Jefferson Davis House |

Richmond, Industrial Center - the James River Canal

James Canal |

Richmond has always been an industrial center because of its position on the James River. The construction of the James River Canal allowed vessels to bypass the falls at Richmond which themselves became a source of electrical power, another impetus to industrialization.

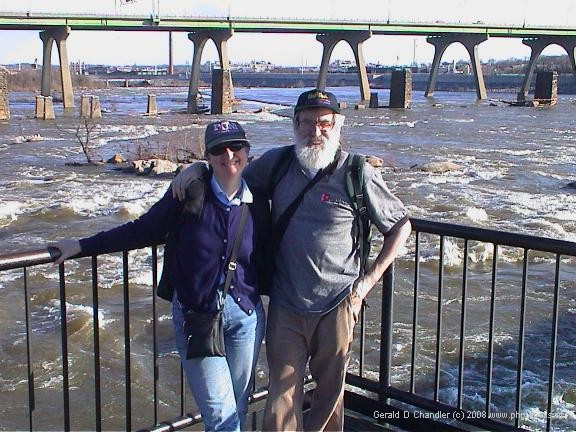

The photos here show some remnants of the canal works that are displayed near the canal, now a pleasant city park; factory buildings bordering the canal, and yours truly with the James River itself in the background.

James Canal |

James Canal |

Richmond is becoming a third capital, a regional one. Its heavy industry has all but disappeared, but is now being replaced with high tech companies that appreciate the quality of life here and its affordability. Richmond easily grows on you. It is big enough to have everything you need and small enough for you to find it. The climate is pleasant most of the year with fairly mild winters but hot, humid summers. As you can see, Gerry was in shirt sleeves in early March.

Bill "Bojangles" Robinson: famous citizen of Richmond

Bo Jangles, jazz musician |

Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1878 and died in Harlem in 1949, Bojangles Robinson worked as a child in Vaudeville but as an adult migrated to nightclub performances and then movies for largely white audiences where he showed off his tap-dancing skills including step innovations like his famous "stair-dance". He is also credited with creating the term "copasetic", to mean AOK.

National Historical Park: Tredegar Iron Works.

Tredegar Iron Works |

While in Richmond, we spent a very interesting morning at the National Park's Tredegar Iron Works, on the banks of the James River. Once the Confederacy's main supplier of canon, the former rolling mill survived the collapse of the secessionist forces and the ensuing burning of Richmond to contribute mightily to the South's reconstruction efforts. But it couldn't survive the transition from iron to steel production in the late 19th century as a national enterprise, becoming a small local operation instead. The buildings were severely damaged by fire in the 1950's before being acquired by the National Park Service and converted to their present function as a historical park.

These photos show the exterior of the old factory buildings, a surviving piece of machinery, and a National Park ranger explaining how Civil-War era canonballs and powder were configured for loading into the cannon. This was only a small part of a much longer demonstration of the work of a cannon crew in battle, that we very much enjoyed.

Tredegar Iron Works |

Tredegar Iron Works |