Home | Front Page | Index | Blog | New | Contact | Site Map

Prague Intro

Old Town

Charles Bridge

Castle Hill

Josephov

North-East

Wenceslas Square

Vysehrad

Vltava

Foto Show

Egypt

Israel

Turkey

Bulgaria

Romania

Ukraine

Poland

Prague

Britain

USA 2002

Travel Map

Prague is a city of about a million people whose historic center, containing less than a tenth of its area and population, is located on the banks of the Vltav. River. It was created in 1784 by uniting under one administration its historic components: the Old Town, New Town, and Josephov (all on the east or right bank of the Vltava) and the Lesser Quarter and the Castle Complex (both on the west or left bank). Of course all of these areas are much older, going back to settlements by Slavs in the 5th and 6th centuries.

The Vltava is a rather short river, only about seventeen miles (28 kilometers) long; in this space it averages a bridge almost every mile; the average is far higher in old Prague. The Vltava ends its short life by flowing into the Elbe River which then leaves the Czech Republic and flows into Germany. Just across the border, about 90 miles to the north north-west is Dresden, through which the Elbe passes and then goes on to the Baltic Sea.

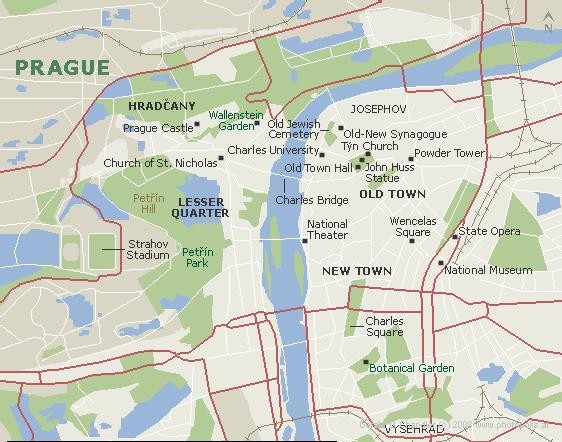

Prague Map with English Names |

Historic Prague is a wonderful place in which to walk. The distances are not vast and around every corner there is a new surprise and a new delight.

A great way to get acquainted with the city is to take a walk that starts near the Old Town Hall, and the John Huss statue, goes west through romantic streets to the Charles Bridge , crosses the Vltava, passes through the Lesser Quarter, and heads uphill to Prague Castle, and St. Vitus’s Cathedral.

This walk, in its entirety, is just under 1.5 miles (2.5 km). A fast walker can do it in 30 minutes. Stopping to visit and savor all that is found along the route could take three days.

While a great introductory route, or one that can be used if time is very limited, this walk doesn't do full justice to the city. It leaves out Josephov, the historic and very interesting Jewish district; Wenceslas Square, now the equivalent of Oxford Street, Fifth Avenue, or Rodeo Road for Prague; and the Vysehrad promontory, one of the most neglected, most historic, and most interesting areas of the city.

Praha Map with names in Czech |

One little problem in learning about Prague is the question of naming: some maps and books give names in English; others in Czech. Initially it can be confusing and one might not realize that the same bridge or river has been mentioned under the two different names rather than there being two different places.

The Charles Bridge, ordered constructed in 1357 by Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, is also know in Czech as Most Karly. The Czech word for bridge is "most" and Charles translates into "Karly". The Old Town, start of the proposed walk, is called in Czech Staré Mesto where stare=old and Mesto=town. The Lesser Quarter, across the Vltava and the Charles Bridge, is known in Czech as Mala Strana, where mala=small/little and strana=quarter/district. Czech for castle or fortress is hrad. Thus the Prague Castle is also known as Prazsky Hrad or simply Hradcany (The Castle) and the older fortess on the right bank as Vysehrad. Good King Wenceslas is called Vaclavske and Wenceslas Square is known as Vaclavske Nam. Because Czech is a slavic language these words are very similiar to the equivalent Russian: bridge=most; old=stare; town=miesto. And finally, Prague is known to its citizens as Praha.

Now let's take our mile and half walk from the main square of Old Town (Stare Mesto) over the Charles Bridge (Most Karly) through the Lesser Quarter (Mala Scala) and up to Prague Castle (Hradcany).

OLD TOWN (STARE MESTO)

Statue of John Huss (Jana Husa) in Main Square |

North side of Old Town Square. |

Prague has a lot of similarities with other north-central European towns, such as Wroclaw, Krakow, and Lviv. All of them had central market squares (Rynok or Rynak) which were the center of economic and political life in the Middle Ages. Old Town Square played such a role for Prague. Today it is still the center of Old Town but the commerce is more ersatz: merchants operate kiosks throughout the square, selling souvenirs and sweets.

One of the most famous and familiar sights in the Old Town Square is the statue of John Huss (1372?-1415). He was a Bohemian religious reformer whose ideas anticipated the protestant reformation by about 100 years. Unlike Martin Luther, John Huss was rounded up and burned at the stake (in 1415) before his movement could take off. As he was Czech, it is worth knowing his name in that language: Jana Husa (also Jan Hus).

All around the square (and in its middle) are buildings of historic note, some quite beautiful. On the north side of the square are Goltz-Kinsky Palace, House of the Stone Bell,and the Tyn Church. The right photo catches a corner of the Goltz-Kinsky Palace. A bit to the right,with a mansard roof, is the House of the Stone Bell. Further right, and by far the largest, in the center of the north side,is Tyn Church. Be sure to go in, perhaps just before going up the Clock Tower.

Old Town Clock Tower

|

Clock Tower Face

|

Even better known and memorable than the John Huss statue is the Clock Tower with its elaborate clock on the lower face and simpler clocks higher up. You should be sure to see one of the hourly performances of the lower clock; you'll certainly not be alone as tourists flock there. We missed it twice by a few minutes before we finally got back to the square "on time."

This giant clock is the antithesis of today's microprocessor clock. Mechanical clocks were first built in the fourteenth century and had to be big because the technology (i.e. precision pieces) was not there to make them smaller. Just as vacuum tubes gave way to smaller single transistors and then to integrated circuits, over about three centuries clocks were refined until they became pocket and then wrist watches.

But long before that happend, in about 1410 the Prague clock (or Horloj or Orlog, to give it a middle ages name) was built. Moving figures were added in 1490. Starting then, and continuing to today (with a long interruption when the clock was damaged), on the hour the twelve Christian apostles appear in the window above the clock face. The clock also tracks the movement of the sun and moon through the zodiac. (Incidentally, in Josephov on the Old-New synagogue there is another distinctive clock: its numerials are Hebrew letters, and since Hebrew is read right-to-left, the clock goes what we normally call anti-clockwise!

View of Old Town and (across hidden Vltava River) Castle and Cathedral |

From the top of the clock tower (admission must be paid and you must arrive when it is open) it seems as if the whole world can be seen. Of course you can look down and see the Tyn Church, St Nicolas Church, and the John Huss statue. And the crowd. On a cold day in December or January there may not be many people. But on a warm spring or summer day, or on a fine evening the square will be overflowing with people.

But look farther. If you look to the west you will see, beyond the broad but hidden Vltava, the Lesser Quarter and Prague Castle. It sits there looking rather small. But later when you approach you will learn how big it is.

St Nicolas's Church on north Old Town Square

|

Narrow street in Old Town

|

Having come down from the Clock tower, head for Charles Bridge (Most Karly). Before you do so, perhaps take another look around the square, and if time allows, take a moment to go into St Nicolas's Church on the north side of the square. Then walk along one of the narrow streets that lead to the river and bridge. There are a few choices — the paths diverge and then merge, but if you keep in mind that you are going west, and keep going west, you easily get there. Or just ask. Everybody about is a tourist and almost certainly speaks English.

ACROSS CHARLES BRIDGE

(MOST KARLY)

Charles IV (1316-78) ordered the construction of his eponymous bridge in 1357, two years after he became Holy Roman emperor. As usual for government contracts, the work was delayed and the bridge was not completed until the early 1400s, a little too late to be of any particular interest to Charles.

The future emperor, Charles of Luxemburg (one of Charlemagne's territories), became king of Bohemia in 1346. At that time, as now, Prague was the main city of Bohemia and was dominated by German nobles. The Holy Roman Empire was really a German thing, set up by Charlemagne. Charles was elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in 1355. With his new power and prestige he set out to make Prague into a truly imperial capital.

Since its opening, the bridge has been the site of scores of gatherings and events, including royal processions, markets, jousting tournaments, and battles. Every so often it has been damaged by a severe flood, but always has been rebuilt. Just last year there were severe floods in Prague. Much of Old Town was under water for a while. Charles Bridge was threatened, but survived intact.

South-east end of Charles Bridge with East Tower, looking toward Old Town

|

It seems a bit harsh to say it, but the Charles Bridge is a tourist trap. You should go, but the weight of the crowd can drown the historic and beautiful atmosphere of the bridge. As you arrive from Old Town you pass the east tower. In times past, this was an important place for guarding the bridge — there were also terrorists, anarchists, and plotters long ago. Today, it is a very pleasant sight to look back and see the tower and the green domed churches just a bit farther back, pleasant, that is, if you can look past and forget the many hawkers around.

South-east end of Charles Bridge, looking toward St Vitus Cathedral and Prague Castle |

Looking the other way, that is, west, you can easily see the spire and roof of St Vitus' Cathedral and below and around it the walls of Prague Castle. Much closer, on the bridge itself, you will see dozens of statues, some of very good quality and beauty. Most are baroque and most were added in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Seek out the statues of Saints Cyril and Methodius. They were the inventors of the cyrillic alphabet; it is named for the first and used for writing most slavic langues, including Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Serb. Poles and Czechs, who ended up Roman Catholic (it wasn't always a happy choice; see what happened to John Huss) also ended up using the Latin alphabet.

Canal paralleling Vltava River, near Charles Bridge |

The bridge is nearly a third of a mile long, so you won't cross it in one blow. At the far end there is another tower. Pass through it and you are on the left bank; you are nearly in the Lesser Quarter. Just before you get there you pass what I'll call the Canal District since I don't know its offical name. Later, after you visit the Castle, if you have time, explore this beautiful spot.

Weir on Vltava River, with view of right bank riverfront buildings near Old Town |

From the bridge or the left bank you can look back at the right bank and just enjoy the serenity.

CASTLE HILL (HRADCANY)

What is most often simply referred to as Prague Castle is really a city within a city. Within its enclosure are numerous buildings and courtyards. The largest single one is St. Vitus's Cathedral, the home of the Prague archdiocese. Running a close second is the Royal Palace with its large and impressive Vladislav Hall. "Out back" is Golden Lane, a street where in the middle ages court workers were housed and made their wares. Saint George’s Square is one of the larger squares and gives a good view of the half-millennium old buildings. Today the Castle buildings contains several museums and the ceremonial offices of the the President of the Czech Republic,

Prague Castle and St Vitus Cathedral above Church of St Nicolas in Lesser Quarter |

Once over the Charles Bridge you are on the left bank and in the Lesser Quarter. For your first visit you should pass quickly through the Lesser Quarter and head up the hill to the Castle. There are several possible routes; don't worry about which and just take whatever turns are needed to keep you going up hill. Head for the west gate, the most impressive one. If you miss going in this way be sure to come out here and admire the gate and the the prospect of the buildings.

Later, when you descend, you can start to explore the Lesser Quarter. Some of the shops along the way offer great souvenirs at very good prices. There are several churches in the area, the largest of which is St Nicolas. This church bears the same name as one in Old Town Square, but they look nothing alike.

From St Nicolas Church (and any place further north in the Lesser Quarter) it is an easy and quick walk to the Wallenstein Gardens. At sometime or other you should get over to this lovely spot meant for lingering. Only five minutes will be long enough to appreciate its fine design. If you have more time bring your lunch or newspaper and sit for a while.

From the Wallenstein Gardens it is easy to find a bridge and walk back across the Vltava to the Old Town. Another option is to take a tram. They come frequently and don't cost much. You should be able to get a free tram, bus, and subway (tube) map in any subway station. When in the station ask about the cost of three day and weekly passes. They are very good deals.

Prague Castle and St Vitus Church from West Entrance |

Western Entrance to Prague Castle |

View from Castle of part of Lesser Quarter, Vltava River, Charles Bridge, Old Town, and TV Tower |

Once into the Castle complex head first for St. Vitus’s Cathedral. Your goal is to go up the bell tower and see the giant bell and then have a view of the city. Afterwards come down and roam about the church and admire it.

Now you have a difficult choice. You really want to see the Royal Palace (Vladislav Hall) but it is too big! You can't see it all in one day, or at least carefully. If you have enough time, enter the museums and roam about and enjoy the stone work and giganticness. If you are tired or hurried and prefer seeing the living, breathing city, skip it. But if you don't care about spending the entry fee to only see part of it, then do go in. You'll be very impressed.

Just by going in the outer gate and looking for the Cathedral and museums you will have already roamed the courtyards. We were very impressed with them, even though the rainy day on which we visited made us dash through them.

Save for last and maybe skip Golden Lane. The houses along Golden Lane were actually built into the castle walls in the 1600s and used as residences and workshops. Today it is similar to the fake streets that you see in Disney World, Covent Garden, and other places "recreated" for tourists. It consists of many tiny rooms, hard to enter and hard to leave, almost all devoted to selling curios. A part is sort of a museum. You should probably decide for yourself if you should go in; tastes do vary.

From the Golden lane you can exit the backside of the Castle compound and head immediately downhill to the river. If you do this you will find youself in the general vicinity of the Wallenstein Gardens. If you don't go down hill this way, go back out (or just over and out) the Western Gate so that you see it and the square beyond. Head west and explore.

Saint Wenceslas (907?-929, in Czech, Svatý Václav), Duke of Bohemia, built the first church of Saint Vitus. (See below for more of his history.) Dedicated in 925 it was only a small rotunda and so was replaced by a larger basilica in 1060. In 1344 Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV ordered the construction of a large gothic cathedral, and work on the present building began. Work on the cathedral stopped 75 years later. The cathedral was only partly finished. In 1872 architects began working to complete the cathedral. Following plans laid out by the medieval architects, modern architects completed the long central hall, or nave, added a new main entrance, and constructed the cathedral’s distinctive twin towers. The cathedral was finally completed in 1929.

For centuries, Vladislav Hall has been the center of activity inside the palace. From the 1500s until the mid-1900s, Bohemian kings and Holy Roman emperors who lived in Prague Castle held court in this grand room. At other times, it served as a social gathering place for nobles. Occasionally, indoor jousting tournaments were held here. In recent times, the hall has been used for important government meetings and ceremonial events. The Czech parliament meets here to elect the president of the republic.

In 1618 Czech Protestants threw two Catholic governors out of the windows of Prague Castle. This act, known as the Defenestration of Prague, helped precipitate the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). The defeat of the Czech nobility at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 led to the execution of 27 Czechs and the exile of much of the Czech nobility. After the victory of Hapsburg forces in 1648, Czechs were forced to convert to Catholicism.

During the 1800s many poor artists and craftspeople lived along Golden Lane. Among these residents was Franz Kafka, one of the most important writers of the 20th century. Kafka lived and wrote in house number 22 from 1912 to 1914.

Prague Castle from Petrin Hill |

An alternate and very attractive way to get to Castle Hill is via Petrin Park and Petrin Hill. If you are starting in the Old Town on the right bank, make your way to the National Theatre and cross the Vltava there. At the end of the bridge you come out just opposite the entrance to Petrin Park. Continue straight ahead into the park. The paths will take you up the hill; where uncertain or there is a choice, veer to the right. Midway up you will pass a recreation area with a tower reminescent of Paris's Eiffel Tower. Nearby you can get a snack if you want.

Continue up and follow an imagined arc first west, then north west, and then north. When you get to the highest point you will have an excellent view of the Vltava and across it, Old Town. And then you will see Castle and Cathedral across a small valley. Continuing on you will pass a nice church, whose name and history I have forgotten.

Narodni Gallery?? near Prague Castle |

Once you have passed completely through Petrin Park you come out at the western end of a street that leads into the western gate of Prague Castle. It gently slopes downhill and passes some magnificent buildings, particularly two on the left (north) side. Unfortunately I can't remember or find the names of these buildings, but they are well worth seeing. If you don't arrive via Petrin Park, then after your visit to Prague Castle leave by the West Gate and walk up hill about 1/3 mile (1/2 km) and enjoy the surrounds. This will take as little as 20 minutes.

JOSEPHOV and JEWISH SYNAGOGUES

The Josephov district is bounded on the west and north by the curve of the Vltava River and is just a hop-skip-and jump from the Old Town Square but for hundreds of years it was considered a separate town. It was a Jewish ghetto for nearly 700 years, from around 1180 or so until about 1850 — the later date being a good 70 years after the incorporation of Josephov into greater Prague. Around the same time it underwent a major transformation with swampy areas (it is near the Vltava River and subject to flooding) filled and many ancient, narrow alleys replaced by a more modern grid of fewer and wider streets.

Old-New Synagogue, in Josephov |

Until the Nazi deportation of Jews to nearby Theresienstadt, where they ran a concentration camp intended to fool the world into thinking Jews were receiving humame treatment, Josephov had a lively and dense Jewish life. Today five synagogues and a cemetery remain of that life. All but one of them is a museum. Together they are the antithesis of what Hitler intended: that a museum be created as the sole reminder of a long disappeared people. Instead they provide a poignant reminder of the strong culture that once resided in this district — and the continuity of Jewish life.

Terezin is the modern, Czech name for Theresienstadt. It is about 30 miles (50 km) to the north of Prague and a frequent day trip for those who have the time. During WWII more than 90% of the Jewish population of then Czechoslovakia died in Nazi run death camps. Those in Theresienstadt for the most part slowly starved. Toward the end of the war the survivors were transfered to other camps where they were immediately put to death.

The Old-New Synagogue (I've forgotten the reason for the name, but I think it was because later there was a new new synagogue) holds services on Friday night. When we were in Prague I attended them; the congregation of about 100 people seemed to be made up of half local people and half Americans visiting. Getting in required going through a security check.

You can get a good idea of the area by walking around and seeing the Synagogues from the outside. Be sure to look for the clock with Hebrew letters/numbers. If you buy a ticket to the synagogue-museums you will get a good introduction to Jewish history. Each building specializes in a different aspect, e.g. Jewish holidays. Save this for your second or third day, if either you have seen what you want of the streets of Prague or it is too cold to be outside.

Old Jewish Cemetery with "Gravemen's Committee" building |

The Old Jewish Cemetery contains about 12,000 tombstones, but estimates of the number of people buried there are much higher. Many graves are stacked on top of one another, and a single tombstone may stand over as many as 12 graves. Adjacent to the cemetery is the building of the committee that ran the cemeteries. The committee formed one of the most prestigious groups in the Jewish community.

EAST of JOSEPHOV

NORTH of OLD TOWN

The north side of Josephov is defined by the Vltava River; the area east of Josephov, south of the Vltava, and north of the Old Town square is a mixture of modern and old buildings. Among them is a large, 10 or 12 story hotel tower, the International, I think, built in the "International" or plain and unadorned style. It is a relic of the sixties or seventies which does not fit in with the older, pre 19th-century Prague. But here and there among these streets there are jewels that makes it worth walking through, if time allows.

To the east of Old Town the land rises into pleasant hills; on the top of them is a large, quite obvious TV Tower. On the lower slopes of the hills, running north-south are the main railroad tracks; south east of the Old Town Square is the main train station. We arrived there from Poland and were met by a man who found an apartment for us on the north-west side of town. A bit to the north of the train station is the bus station. There we left Prague after a fine five days, taking an overnight bus to England.

Now let's get to the things worth seeing: the Powder Tower, the Art Nouveau auditorium, and the National Museum.

Church northeast of Old Town and Josephov |

One way to see the north-east is to start in Josephov and walk clockwise in a sort of semi-circle. If you do this you will start by seeing a nice square with a church.

Hotel Casa Marcello exterior, east of Josephov, north of Old Town |

After going somewhat farther east you might be on a route through a small street that takes you past the Hotel Casa Marcello. When we walked by it we immediately said that it was a place where we would like to stay. It costs at the top end of the scale, so we thought maybe someday when we made a return trip we would stay there. (On the other hand, we had absolutely no desire to stay in the "International" hotel.)

Powder Tower |

I wish I could remember the story of this tower, but I can't. But don't miss seeing it. If you don't have time for the "east" walk, just make a quick jaunt over from Old Town Square and back. The connecting streets are a pleasure to pass through.

Art Nouveau decorated theatre, near Powder Tower |

This building is well worth an inspection. Check out the highly decorated interior. And check out the offerings. Maybe you'll find an event you want to attend, although they are a bit pricey.

From here it is an easy walk to the south-east end of Wenceslas Square. If you have done things in another order and have just seen Wenceslas Square you can easily walk over to the theatre and Powder Tower.

WENCESLAS SQUARE

(VACLAVSKE NAMESTI)

When thinking about Wenceslas Square don't be too literal. It is not square at all, but rather a broad avenue about 4/10 miles (700 meters) long. Over the years it has had many changes. Once upon a time people used horses for real work. And, as should be obvious, they bought and sold them. In that day and age the Horse Market was located here. As you visit it, imagine a lot of mud, straw, and horse droppings. With modernization, and as everything got up to date in Kansas City, so did it in Prague. Horses and horse market went, and trams were laid down the middle of the avenue. And then trams went, a greenway was put down the center, and the "square" took its appearance of today.

Wenceslas Square seen from National Museum steps

|

From the steps of the National Museum you get a look down almost the entire length of the square. At the top end is the statue of King Wenceslas on horse back. As Jan remembers it, when she visited in 1968 the square looked closer to a horse market than an upmarket for yuppies. Not really, but it certainly didn't have the wealth and elegance on display that it does now. It was rather bare, and grim looking, although part of that may have been the season (November).

If you can, imagine the square filled with nearly half a million people, all protesting the Soviet forced ending of the Prague Spring. This is where it happened. Briefly, the history is as follows: In January, 1968 Alexander Dubcek became General Secretary (head) of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party. Rather quickly he put into place ideas that he had been developing for years. These included almost complete freedom of the press, something absolutely absent in all other eastern European and communist countries. He was called to Moscow by Brezhnew and told to rein in things. When he didn't, the USSR and its "allies" (i.e. satellites) sent masses of tanks and other forces into the country. The peaceful opposition failed and freedom was suppressed until the breakup of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact in 1989-91.

Statue outside National Museum and top end of Wenceslas Square |

Outside the National Museum there is a statue that overlooks Wenceslas Square. That is as close as we got to the inside of the Museum. Thus we can't evaluate how good or interesting the collection is.

Brits strolling outside shops facing Wenceslas square |

These guys were part of a football team or something similiar. I didn't talk to them but it was obvious they were enjoying Wenceslas Square. Not shown is the other side of their costume: each one had a plastic sheet over his rear in the form and color of a bare ass.

Lining both sides are plenty of high priced and high quality shops. Most hours of the day the sidewalks team with people. Most of them are tourists, but a few are shills trying to gyp tourists. One of their games is to offer to change money at a particularly good rate and then give a worthless currency that appears to be, but is not Czech money.

The Story of Saint Wenceslas (Svatý Václav)

Nearly every English speaker has heard of "Good King Wenceslas" because of the popular 19th century Christmas carol. Although there have been many Czech/Bohemian kings with this name, he was the first, and the one for whom Wenceslas Square is named.

He was born near Prague about 907 and died in Stará Boleslav, Bohemia, in 929. In his brief life, of only 22 years, he obviously impressed himself on his country as he became the patron saint of Bohemia and Moravia,

Wenceslas was raised a Christian by his grandmother St. Ludmila, but his ambitious mother, Drahomíra (Dragomir), a pagan, had Ludmila murdered and acted as regent herself until Wenceslas came of age in 924 or 925. Her court intrigues and the wishes of the people to end the conflicts between Christian and non-Christian factions in Bohemia led Wenceslas to take the reins of government. As Duke he was pious, reportedly taking the vow of virginity, and encouraged the work of German missionary priests in the Christianization of Bohemia. His zeal in spreading Christianity, however, antagonized his non-Christian opponents.

Faced with German invasions in 929, Wenceslas submitted to the German king Henry I the Fowler. His submission provoked some of the nobles to conspire against him, and they prompted his younger brother, Boleslav (Boleslaus), to murder him. Waylaid by Boleslav en route to mass, Wenceslas was killed at the church door. Frightened by the reports of miracles occurring at Wenceslas' tomb, Boleslav had his remains transferred in 932 to the Church of St. Vitus, Prague, which became a great pilgrimage site during the medieval period. Wenceslas was regarded as Bohemia's patron saint almost immediately after his assassination.

VYSEHRAD

It is hard to define when Prague was first settled, but it seems accepted that the right bank castle, Vysehrad was built before the left bank castle-church compound, Hradcany. But once the powers that be had moved to Hradcany the 9th century Vysehrad became something of a backwater. Today it is a park that contains a cemetery where many of Bohemia and Moravia's greats are buried. There is a rather beautiful church dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul. Because of its site on a commanding hill (i.e. military site) above the Vltava it has beautiful views. Opposite the church there is a nice restaurant at which we ate.

On your third or fourth day, if the weather is fine, spend an afternoon at Vysehrad. You can get there by walking from the Old Town, but it would be better to take a taxi or tram to get you closer. Arrive in time for lunch at the restaurant overlooking the river. Then tour the cemetery. Afterwards walk down the hill into the non-tourist area at the bottom of the hill. Then, if time and weather allow, walk along the Vltava north into the Old Town.

Sign to Vysehrad. ("National Culture Patrimoni?") |

Column with Byzantine mosaic face, Vysehrad |

View south of Vltava River from Vysehrad viewpoint |

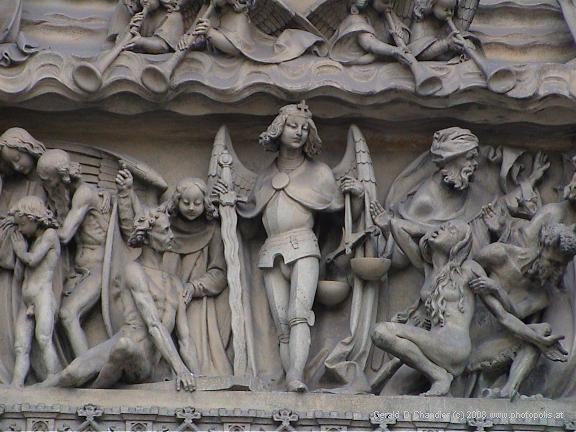

Frieze decoration, church in Vysehrad |

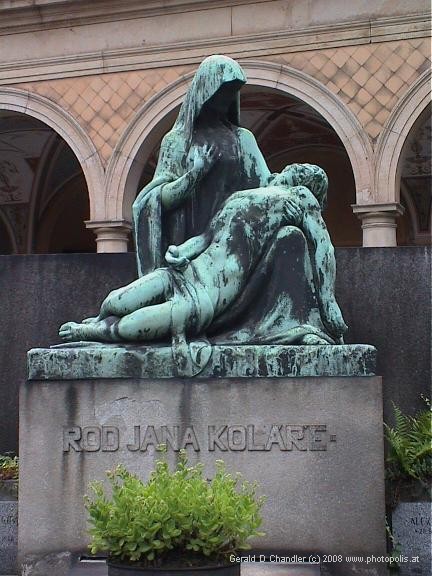

Grave decoration, Vysehrad cemetery |

Grave statue, Vysehrad Cemetery |

ALONG THE VLTAVA

There are many beautiful buildings along the Vltava waterfront, but in Jan's opinion the Frank Gehry building is not one of them. Gerry thought it interesting, but Jan found it was just an ugly intrusion among all of the lovely period buildings around it. It would have been better to build it in a modern suburb as a relief and contrast to all of those ugly sixties buildings that abound in such places, but not here amongst all this beauty.

Frank Gehry "Twisted Bottle" building, near Vltava River. |

Old Water tower, Vltava River |

If you do walk along the river bank you'll also pass the Czech National Theater. The ornate building was constructed between 1868 and 1881, primarily with funds from private citizens. Shortly after the first performance in the theater, a fire destroyed much of the building. After the fire, however, Czechs demonstrated support for a national theater once again, raising sufficient funds to rebuild the theater within two years.

Czech composer Bedrich Smetana’s Libuse, an opera about a legendary Slavic princess, opened the inaugural season in the newly rebuilt theater. The opera, composed for the occasion, concludes with the princess Libuse’s prophecy: "My dear Czech nation will survive!"