Home | Front Page | Index | Blog | New | Contact | Site Map

Paris 1999 | Maps | Pics Day-by-day

Tourism

Daily Life

71 Rue de La Mare

Belleville

Computers

Metro

Objets Trouvés

Events

Gerry's Sketch

Hen Party

Jan's Birthday

Tour de France

Outings

Outside Paris

Fontainebleau

Giverny & West

Solar Eclipse

Versailles

Paris 1999

Paris 2005

Paris 2007

France 2007

Paris 2008

France 2008

Britain 1999

Beijing 1999

China 1999

Hong Kong 1999

Vietnam 2000

China 2000

An interesting subcategory of museums might be called ego-museums. They have the property that their founders created them to either display either their own work or their own collection. "Ego" may be too strong a word, because often the founder was attempting to perform a genuine public service. Paris has its share of such museums and we visited five of them.

Several are in so called "Hôtels", using the old French word for a rather elaborate mansion. A common feature of these Hôtels is that on one side of the mansion proper there is a "cour d'honneur" with a horse-shoe drive for the arrival and departure of carriages. On the opposite side there is a large garden. The Palais Bourbon, which now houses the French National Assembly follows such a pattern and could be considered the hotel of all hotels.

Two museums that are worth mentioning also fit the pattern of ego-musems. We didn't visit this time because we'd already gone, and they really shouldn't be missed. Both contain such fine and famous works that unlike other ego-museums the short-term visitor to Paris just must see one or both on the first trip.

The Hôtel Salé was built in 1656-59 in the Marais district, then the home to the rich, as the residence of Pierre Aubert de Fontenay. It was paid for largely from the proceeds of the salt tax which Aubert was in charge of; hence its name, which means salty or salted. After passing through many private hands and then to the government, it ended up as a school and became very run-down. While André Mauraux was Minister of Culture in the 1960's a law was passed allowing inheritance tax for artists to be paid with their works. Picasso's family gave hundreds of canvasses; the government fixed up the building; and thus was born the Picasso Museum in the Hotel Salé.

On the other side of the Seine, on the left bank, near the Invalides, the Hôtel Biron was built in 1728 by Abraham Peyrenc. Presumably he paid for it from the proceeds of his wig-making business. They were a big deal in that day and age. Like the Hôtel Salé, the Hôtel Biron also changed hands many times and decayed. Part of it, rather than all, became a lycée, which remains to this day. The other part was loaned to a famous artist to use until his death, in exchange for part of his works. In effect, an informal version of the Malraux inheritance law. Thus was born the Rodin Museum.

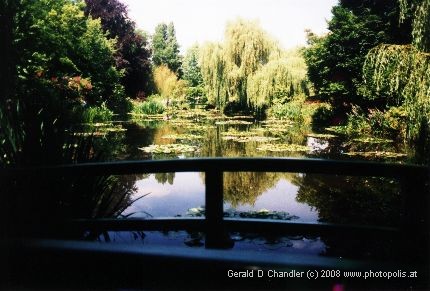

Monet's Giverny Pond |

On our second day in France we made a trip to Giverny, about 50 miles west of Paris to see Claude Monet's museum. We'd been in the village in 1994 but had arrived there about 6:00 p.m. and had only been able to visit the grounds.

Claude Monet was born in Honfleur, on the French coast. In his early years as a painter he was desperately poor and several times begged that his paintings be bought so that he could pay his debts. In later years he was very successful and bought a large house and workshop in Giverny. It was there that he built his Japanese bridge and painted his water lilies. Since his death it has become a pilgrimage site. Since it has very few of his works on display it almost doesn't qualify as an ego museum. Many more are found at the Orsay Museum and at the Marmottan Museum.

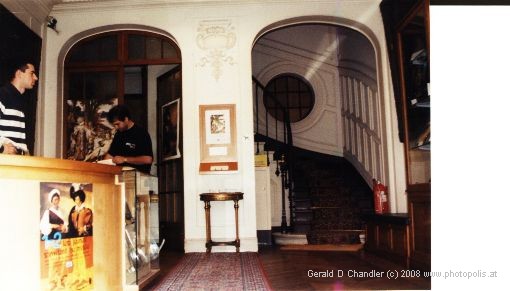

Gustave Moreau Museum |

One that does qualify, without a doubt, is the Gustave Moreau Museum. We first became conscious of Moreau in New York in the weeks before we left for France. His paintings are highly symbolic, very crowded, and filled with dark colors. They please some; Jan is among them. We visited an exhibit of his work at the Met in New York City and learned that he had converted his house in Paris to display his own works. We were so intrigued that we determined to visit it, and did so. Only a ten-minute walk from the Opéra Garnier and the largest Paris department store, it sits on a very quiet street with no traffic, surrounded by mansions that have been converted into offices or banks and the like. The building was originally only two stories and was a wannabee's hôtel: it had a small courtyard in front and a garden in back. Moreau enlarged it by doing away with the front courtyard and adding two stories. At his death in 1898 he left more than 6,000 works with instructions that they should always be displayed exactly as he left them.

Jacquemart-André Home and Museum |

Another museum whose founder said, "leave it as it is" is the Jacquemart-André Museum. The only other similarity with the Gustave Moreau Museum is that it too is in a hôtel, but a much better one. Unlike most museums in Paris, it is private, and it advertises to get vistors; that's how we heard of it. We were delighted to be there. Edouard André was a rich banker who employed Nellie Jacquemart to paint his picture. Love and marriage and a passion for art ensued. At the time they married Haussman was re-making Paris. The trace of the old city wall became a modern boulevard and on it the couple built in 1865-1869 their own palace. And they filled it with 18th-century French and Italian renaissance treasures. The result matches their egos. The house is very unusual in one respect: Front and back are inversed. Visitors go through a tunnel/arcade to get from the street to the other side of the house. There they are in the Cour d'honneur and go in the main door between two terraces.

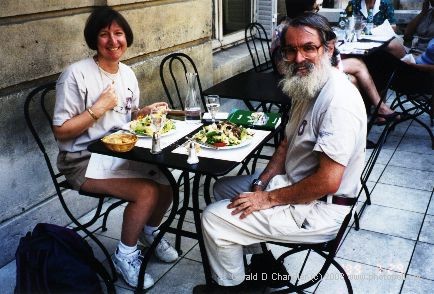

Lunch on the Terrace, Musée Jaquemart André |

After our tour we ate on the terrace and enjoyed the fresh air.

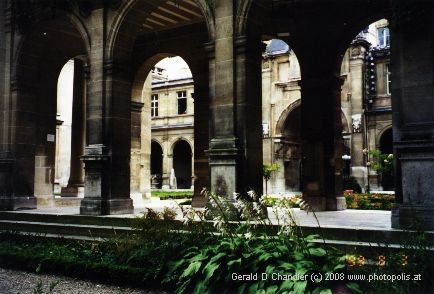

Musée Carnavalet |

An entirely different story is the Musée Carnavalet, the museum of the history of Paris. It is housed in the finest, in fact, two of the finest hotels mentioned so far. It is also in the Marais, not even a five minute walk from the Hôtel Salé in one direction and the Place des Vosges in the other. One of the two hotels is the Hôtel Carnavalet, (two of the courtyards are shown) built in 1548 but reaching its current form in 1655. It passed through many hands and eventually became the City of Paris' museum. But the collection is so vast that the nearby Hotel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau was made part of the museum in about 1985. We spent a long day there, going out for lunch to get some rest, and then coming back. Unfortunately a command of French is needed to really enjoy the museum, but if you can read French then the captions to the wonderful collection of 14th and 15th-century paintings will be a marvel. The coverage of the French revolution is also great.

When Gerry's aunt Zelda visited she mentioned that she would like to go back to a museum that she had seen in Paris about twenty years ago. She could remember that it was in a residential neighborhood, near the Bois de Boulogne, and contained a wonderful collection of impressionist paintings. We had never heard of such a museum, but it turned out her memory was right-on — if incomplete. We scoured our maps and eventually concluded that she must be referring to the Marmottan Museum. When we visited we found that not only did it have one of the largest collections of Monets in the world (acquired when Monet was penniless) it also has a collection of bible illustrations and an impressive collection of French furniture of 1800-1850. The Marmottan rates inclusion among ego museums not just because it is a private home that became a museum, but because it also has the works of the impressionist Berthe Morisot and her children and their children, who once owned the house.

Because we had been to the Marais to walk about and see the Carnavalet, Place des Vogses, and other places, we learned about the Cognacq-Jay Museum in the Hôtel Denon. From its windows one can see the back of the Carnavalet. The Cognacq-Jay houses a rich collection of paintings (including a Rembrandt and two Canalettos), much period furniture, a fine collection of German porcelain, and itself is a very interesting hôtel. Like the Jacqemart-André it also takes it name from Mr and Mrs, and also houses the collection the couple amassed in their lifetimes. Unlike the Andrés, the Cognacqs never lived in the building that eventually housed their collection. Mr Cognacq is the founder of the Samaritaine Department store (and thus of department stores); he became rich and created a museum to add to the world's enlightenment. At his death it was given to the nation. Eventually it was moved from its original location to its current one.